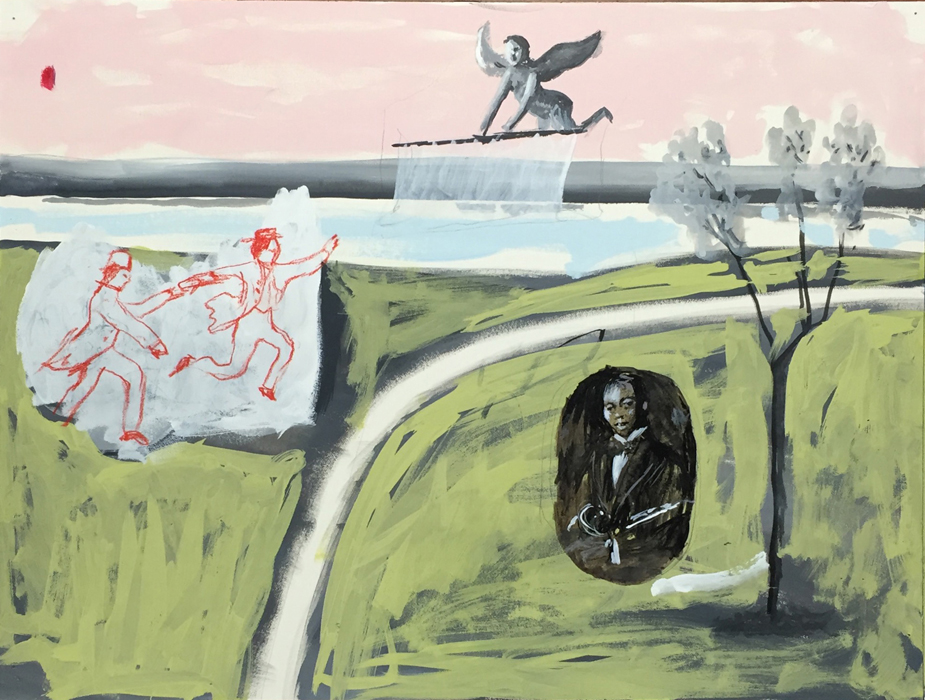

Natchez Bluff

Noah Saterstrom | gouache on paper on masonite | 12″ x 272″ (in 17 panels) | 2016

Natchez Tricentennial Celebration, Historic Natchez Foundation, Jan 28 – Feb 28

*Scroll right (or see below) to view full frieze

The high stretch of bank overlooking the Mississippi River along what is now Broadway Street in Natchez is referred to by locals simply as the Bluff. Designated for public use by the Spanish in the 1700’s, it has been protected as a promenade ever since. My grandparents lived at a house called Edelweiss which sits at the top of Silver Street, looming over the bluff and the water beyond; there is no view in the world more familiar to me than the River from that vantage.

This “Natchez Bluff” painting is a tribute to the many and varied lives lived along the physical bluff from the advent of civilization in the area to the days I picnicked there with my family. It includes both the wartime atrocities that carved the human history of the cliff and the leisure class strolls that have had the panoramic view of the River as a backdrop.

I also use “Bluff” for its other meaning: deception, pretense, facade. Historically, any celebration of Natchez was a carefully curated, fanciful, whitewashed depiction of what the original Natchez Confederate Pageant program calls the “halcyon days before ’61.”

The Natchez that I grew up in indeed appeared bucolic and serene, a slow waltz choreographed by an old Mississippi ancestry that left a legacy of aristocratic self-worth without any actual wealth. My experience of Natchez was guided by Victorian principles that valued formality, elegance and politeness, often at the expense of honesty. I felt society (outside of my immediate family) was hostile to difference and there was a silent, relentless reinforcement of class roles that left me with a vague unease. Despite that somewhat sinister undercurrent, for me life in Natchez was essentially safe and beautiful.

I lived the life of that powerful, crumbling ruling class aristocracy, and therefore, I know I am fundamentally unable to truly see Natchez from any other point of view. And as we see, not just in Natchez, or in Mississippi, or in the South, but all over the country, those with privilege (mostly white people – and of course I include myself) are ignorant of the extent of their privilege and the obstacles others face. The best we can do is to listen, closely and without preconception, to the stories others tell in an attempt to make delicate work of incorporating narratives other than our own in the service of honest exploration and exposition.

In researching for the making of this piece, as I talked with people about their memories, sifted through photography archives, and read of life on the Bluff, I was struck again with the fact that there is not one Natchez, but many. The outline of these realities, too, is not sharply hewn, nor is it split evenly between races; rather, it exists on an overlapping spectrum of lives lived. All whites did not experience the same town, neither did all blacks, and it is, I think, damaging to simplify in either direction.

Yet, regardless of these extant complexities, only one version has often been used to portray the town – or rather, one version of one of the versions of Natchez.

If the only voice in town is the remnant of a nostalgic aristocracy, the best we can hope for is illusion and romance. Songbirds and fragrant honeysuckle.

Fortunately, the old regime of Natchez, which would have only told one story, is now, and increasingly, accompanied by many new voices. I hope to add my own with its insistence that it is possible to celebrate Natchez by focusing on the real town, its actual history and complexity, and not reduce it to fiction.

For a town so small and remote, it is a place of great national contradiction, known for enormous wealth and devastating poverty, elegant sophistication and stark brutality.

The town draws some people in as it simultaneously shuts others out and keeps many down.

It has transcendent physical beauty; it is a tapestry of natural features and those created by centuries of human hands.

It is a region shaped by devastating effects of greed, fear and human ignorance: DeSoto’s ruinous arrival. The French colonist’s decimation of the Natchez Indians. The massive and brutal slave trade. Jim Crow era oppression.

It has witnessed natural tragedies in the scourges of Yellow Fever in the 19th century, and the Great Tornado of 1840 while succumbing to catastrophic human errors, like the thousands of unnamed, unmarked dead at the so-called “Corral” contraband camp during the Civil War and the hundreds of revelers burned in the Rhythm Club fire of 1940.

My intention and my hope is to focus not only on the difficult stories of Natchez, nor the crumbling aristocratic facade, but to work with the richness and contradiction to pave avenues of reflection and recognition. Art, according to some, is best used to open questions, to lengthen the resonance of those questions, not to answer them.

While it is perhaps not entirely deceitful to show Natchez as the romantic home of the antebellum planter class, it is a problem to show nothing else, as was once the case. We can and should rejoice that things are changing, stages are opening, and narratives are expanding; this new reality, in itself, is a cause for celebration.

– Noah Saterstrom, 2016

***

Deepest gratitude to the Historic Natchez Foundation and the Tricentennial Committee for inviting me to show this work. And I’d also like to thank those who helped me research and offered their personal stories without hesitation: Antionette Thompson, Wesley Nichols, Ruth and Charlie Powers, David Abbott (Mississippi Dept of Archives and History), David Lowe (New York Public Library Photography Archive), Mimi Miller (Historic Natchez Foundation).

The painting is dedicated to my grandparents Margaret and Theo Wesley.