Uncategorized

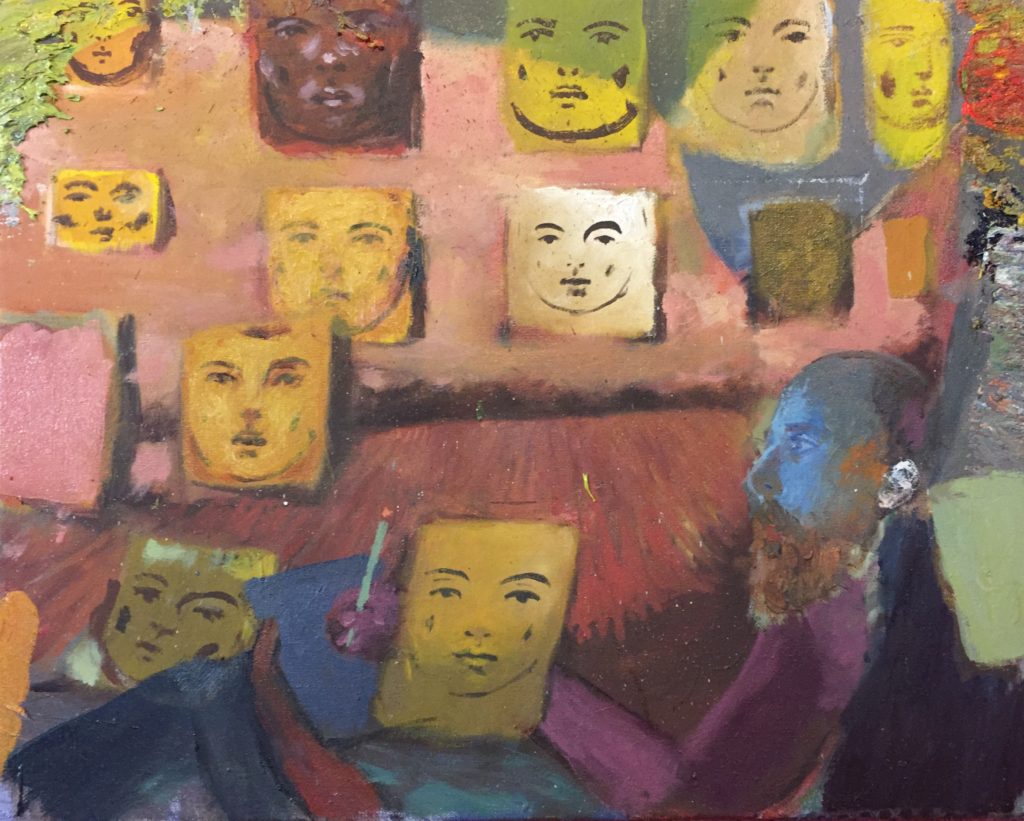

Gathering

Agatha Christie

Janis Joplin

Jump

Oh Little Liza

Workaday Sale

The Workaday Spring Studio Sale is on right now. Over 200 works on paper and canvas are available, moving works from my studio to loving walls. Search by price. If you want to reserve anything for yourself or have any questions, please email me at noahsaterstrom@gmail.com

Related Images:

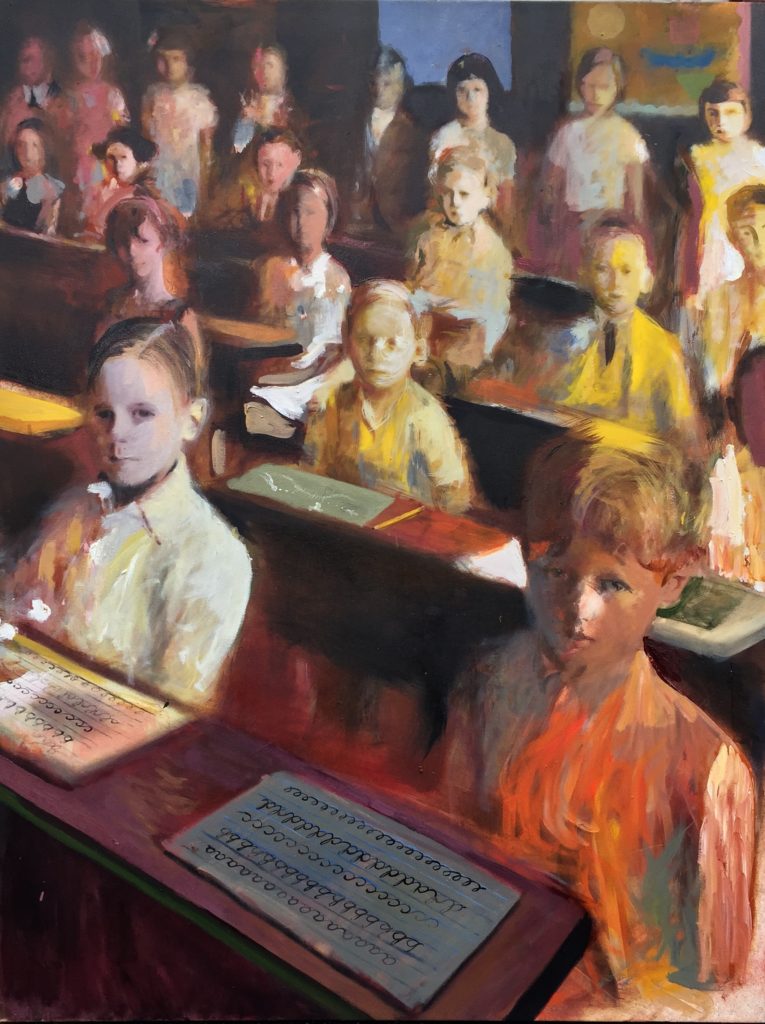

School of Expression

Pledge of Allegiance

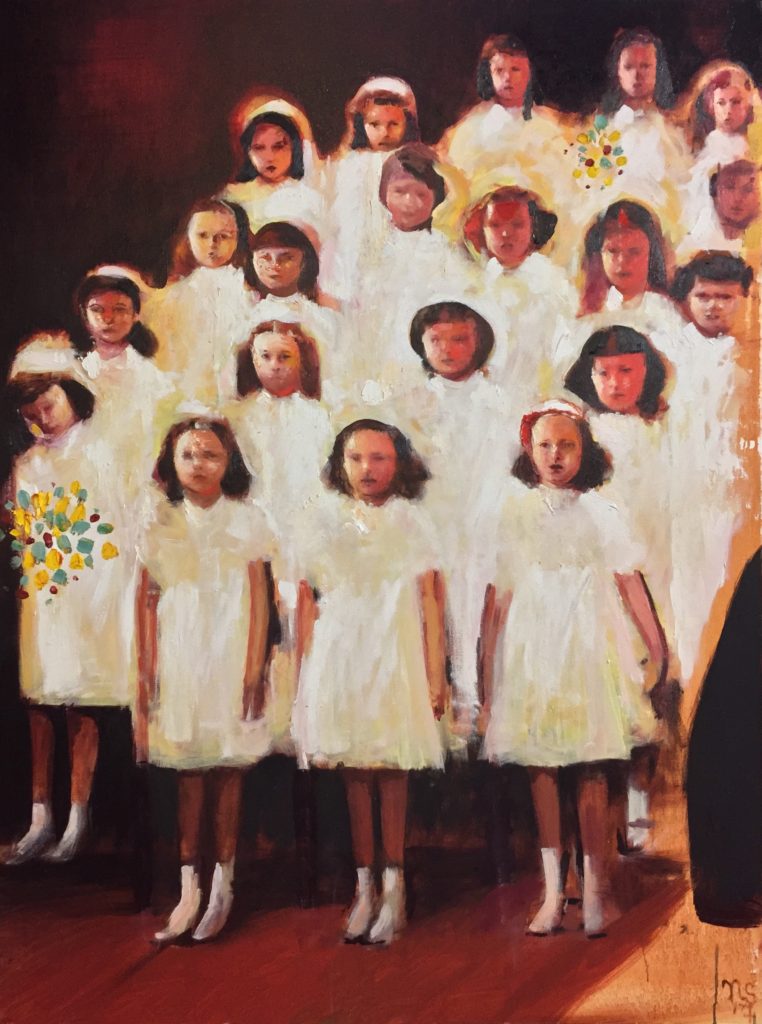

Our Lady of Lourdes

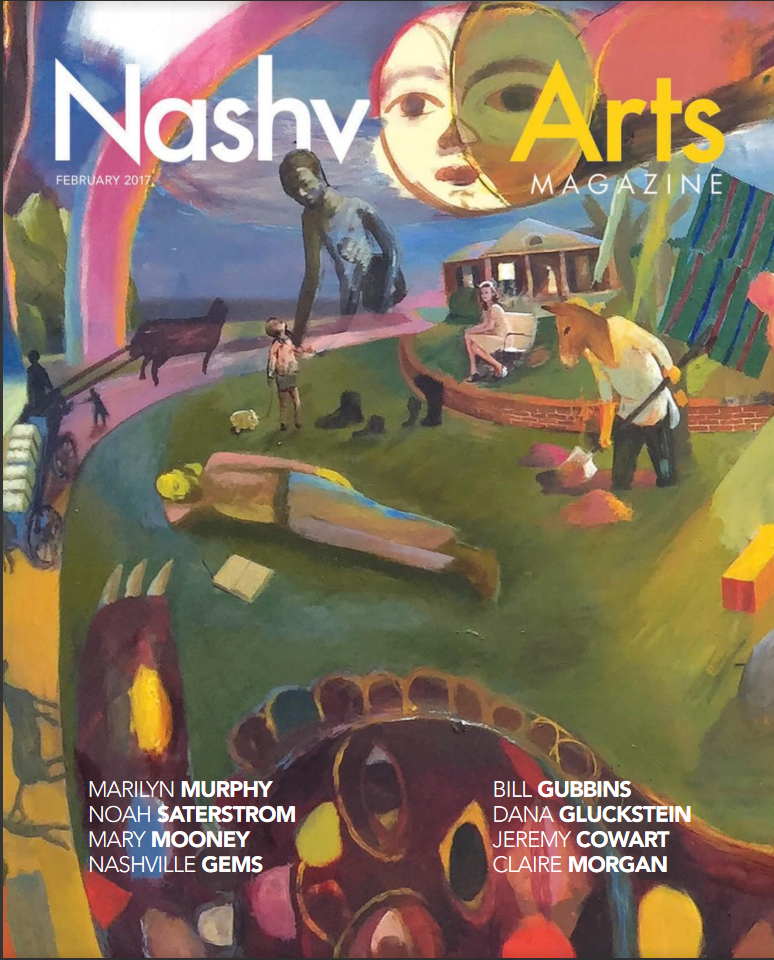

Nashville Arts Magazine, Feb 2017

I am deeply honored and excited that curator Jochen Wierich wrote this eloquent article about my exhibition — Shubuta & Other Stories — for Nashville Arts magazine. Click the link below to read the full article (p.58-63).

Nashville Arts, February, 2017

“Two Converging Paths Into History”, by Jochen Wierich.

The exhibition is up until Feb 15 at the Julia Martin Gallery in Nashville.

Related Images:

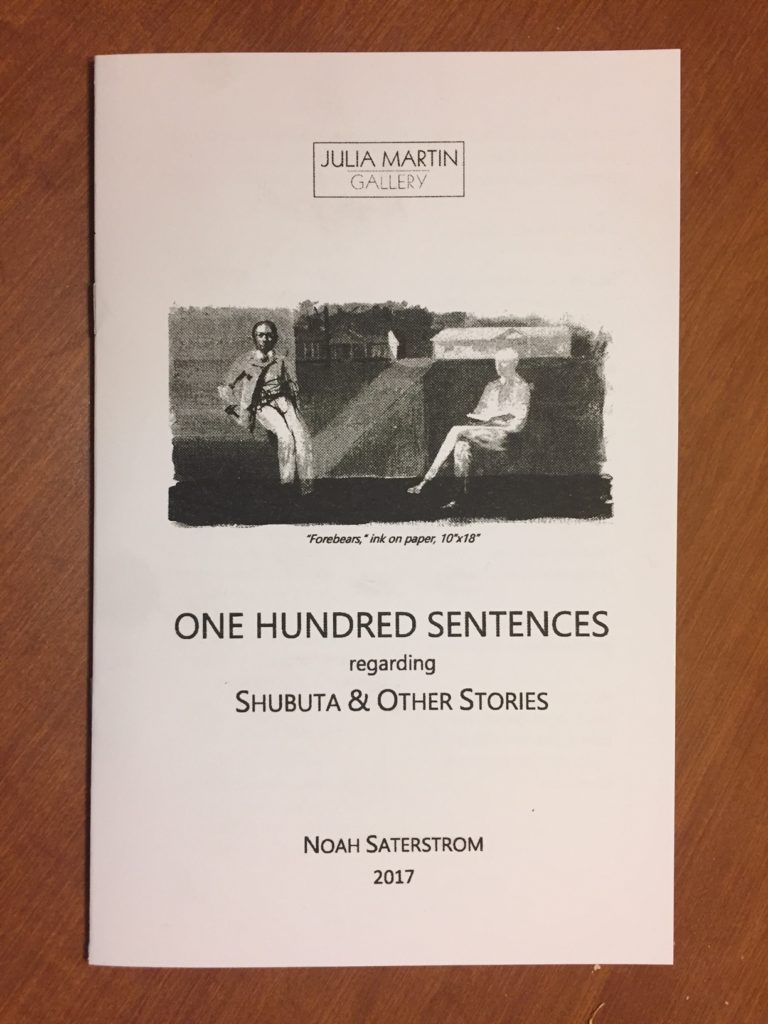

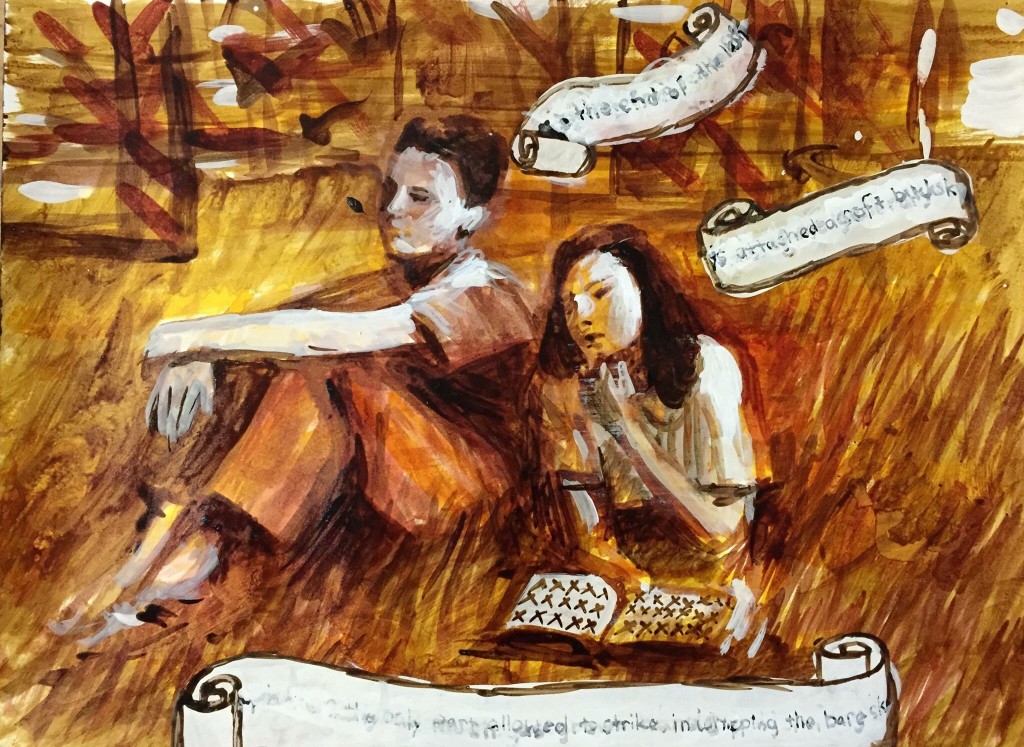

100 Sentences

For my current show at the Julia Martin Gallery, I put together this little book of one hundred sentences about painting, history, slavery, memory. I don’t think that these, or any other paintings require text, but this show includes many detailed references. Thought it best to document them, for what it’s worth.

ONE HUNDRED SENTENCES

Regarding SHUBUTA & OTHER STORIES

NOAH SATERSTROM | 2017

It may be understood that paintings are always primarily about painting.

Certain themes persist.

Maurice Denis tells us to “[r]emember that a painting – before it is a battle horse, a nude model, or some anecdote – is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.”

I did not set out to paint about slavery, or bigotry

I did set out to paint about family stories and place.

The family stories are mine and the place is Mississippi.

What is unique about the South is not racism, not even its institutionalization – you can find that in the North, too.

Celebrating difference does not come easily for humans, even if recognizing difference does.

What may be unique about the South is its specificity regarding racism.

My family in Mississippi owned thousands of slaves.

There are records, signed contracts, inventory lists.

In 1828, my mother’s mother’s mother’s father’s father’s father was Governor of Mississippi and proposed to legislators that there be no more slaves brought to the state and the practice, “an evil at best,” should be ended within a generation.

They didn’t go for it.

In a state record of 1860, thirty-two years later, his own son was listed as owning 512 slaves.

I do not recount this to condemn my family.

Having slave-owning ancestors doesn’t make you a racist, but being a slave owner does.

Being an artist doesn’t free you from bias.

I am interested in making paintings, not in making social statements.

I’m not even interested in making artist statements.

The financial benefits of slavery were not enjoyed only in the South.

Bigotry is not a rural phenomenon.

I am interested in family, memory, history, my own and others’.

I could look at other people’s family albums all day.

Specificity pulls me in.

Questions arise from stories, both factual and apocryphal, passed from mother and father to son and daughter.

Want to pull out an old slide carousel?

We have all night.

Should art be interrogatory, not declarative?

One has a certain fascination with unresolvable questions.

Thousands of slaves were owned by my ancestors.

I don’t know how many stayed in Mississippi.

Presumably tens of thousands of current residents of the state are descended from people once owned by my family.

Painting is about capturing.

Storytelling is about preserving.

I don’t know if that’s true.

No, drawing is about preserving.

The Corinthian girl so long ago traces the flickering shadow of her lover on the wall before he left for war.

There is a case to be made for preservation.

Or is preserving always romanticizing?

You guessed it, he didn’t come back.

We know romanticizing to be hazardous.

We know a romantic past is a daydream.

When we long for a lost paradise, what we mean is our garden was taken from us.

“We didn’t surrender the good times, they were stolen.”

“There were the good times, and now there is now, and someone is to blame.”

“It was an economic decision.”

“They didn’t hate their slaves”.

“The field hands were a good investment.”

The house servants tended to their daily needs and to their children.

If you want to say something good, use your words.

No, better to use your actions.

Is there anything less significant than a history painting in the 21st century?

Paint can do very little beyond itself.

If you want to do some good in the world, have an apple.

Walls are for collectors.

It is good to look at paintings quietly, daily, over a period of years, decades, generations if possible.

There is a dimension beyond what can be experienced at this moment, and it’s called make-believe.

Images are resolved formally not conceptually.

Imagery propagates itself.

We were taught that my mother’s family were intellectuals, philosophers, scholars, doctors and planters.

My great great grandfather, a child during the Civil War, remembered how the black Union soldier stationed at their home to protect them from jayhawkers and bandits during the chaotic time of the federal occupation of Natchez would whittle toy bayonets out of cane for the little boy to play with.

They played soldiers; well, one of them was playing.

He grew into a respected man, one people thought of as good.

While a law student at the University of Mississippi in the 1880’s, he and his friends on a lark held a mock trial of a young black man they met on a bridge.

For fun they held him, made up his crime, and convicted him right there on the bridge.

After the fun, they sent him on his way into the night.

In the 1930’s he referred to the Klan as a “necessary evil.”

“Servants” ” nurses” “maids” and “drivers” feature marginally

in family letters, always with nurturing and friendly feelings.

Black people were often the last to see my ancestors alive.

Sam Brown, my great great grandfather’s great grandfather’s “trusted body servant”, was with him when he died beside his horse in 1823.

This continues right up to Wilfred, the yard man, my grandfather’s last hospital visitor.

And again to Sandra, the caretaker of my aunt and grandmother, both recently passed.

There may be little to glean here but interconnectedness.

In the minds of many white Southerners was not hatred of black people, but restoring the “previous social order.”

And fear, of course.

The previous order was seen as balanced, prosperous, natural.

As it happened, that previous order relied on white supremacy.

Memory is the same as History, just shorter and confined to one person.

History is the same as Memory, just longer and more crowded.

Both have unreliable narrators.

To intervene is to come between.

To interfere is to strike between.

Some are highly controlled and intentional, while others are improvisational, gestural: paintings, I mean.

I grew up mostly in a small river town whose system of race and class distinctions were strictly enforced by the ruling class.

Of course neither this town nor its system are special for that.

Is there any value in painting about something that even words — arguably a much more efficient medium — struggle to describe?

My work is finding a way to make paintings that are analogous to the way my mind works.

Not because the world needs to see how my mind works but if my painting is like my thinking, it will come without obstruction.

What artist doesn’t want that?

I recall Philip Guston’s long, long preparation for a few moments of innocence, and then I name my son Guston.

Trying to speak plainly about an uncomfortable subject is at least an alternative to catastrophic politeness.

On Sept 16th 1841, one of my ancestors gave $34.25 to his wife’s father to rent his servant William for three months.

After that they agreed he would be on loan as needed until April for $10 per month – about $263 today.

Painting can kick off involuntary thoughts and dreamlike associations in the brain.

For some, this is enjoyable.

The world needs good deeds to be done.

Painting does not do that kind of good in the world.

If I were raised on the ocean, I might paint what I observed about the waves.

If I were raised in the trees, I might paint what I knew of the canopy, of birds and bugs.

In real stories, everyone is human.

***

I would like to thank Julia Martin Wimmer, Sam Dunson, Jochen Wierich, Jessica Eichman, Anna Saterstrom, and Jules, Vivi, and Gus Saterstrom for encouraging me to make and show this work.

Shubuta & Other Stories is dedicated to my family.

Related Images:

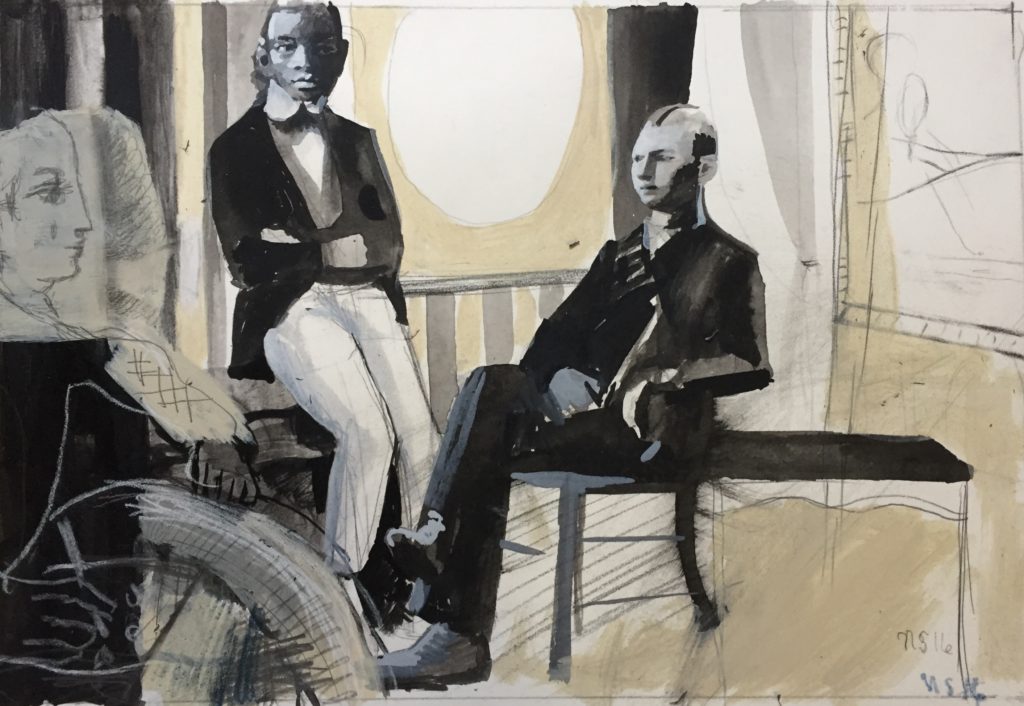

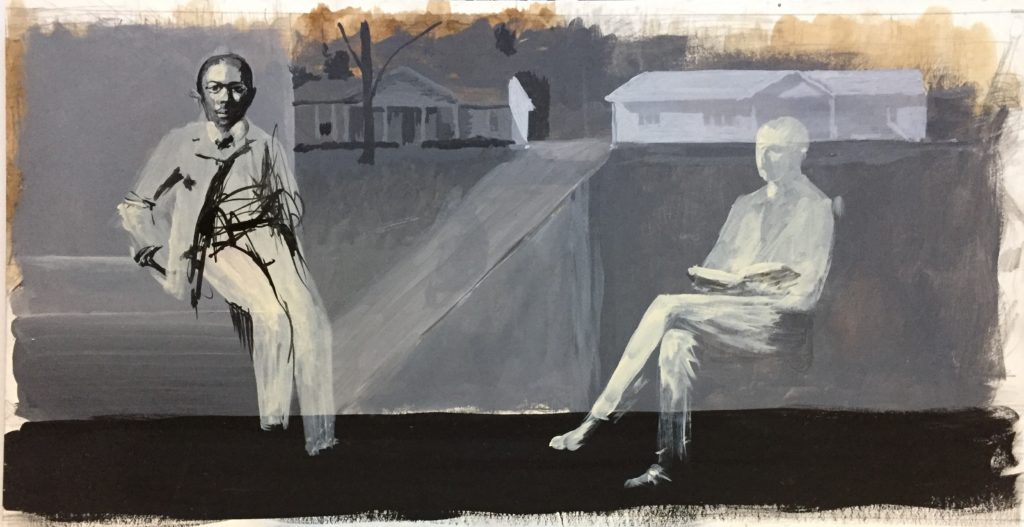

In Times of War

Renting William

Sam Brown

Cutting Bayonets

Bed Barges

Cutting Bayonets

Girls in Shrubs

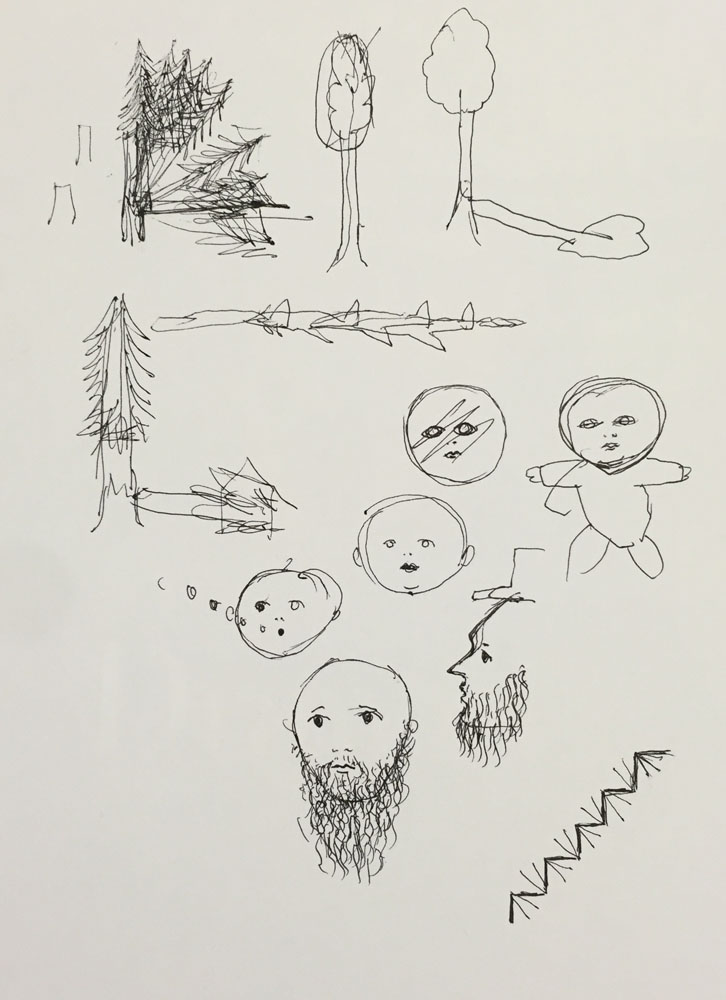

Drawing Faces

Projection

Two Figures

Pupils and Bees

Pupils

Orphans & Hornets

Orphans & Ribbons

Orphans & Bees

Prosperity Cake

Wish You Were Here

Tails

Marco Polo

A One and a Two

Songs for Sundays

Did You Ever Watch a Moonbeam

Personhood of Farms

Flo

Lylah’s Bus

Wish You Were Here

Personhood of Birds

Pirate’s Cove

Out from Penn Station

Hayfield

Natchez Bluff (panel 17)

XVII.

The two children (“the Wastrels” as I call them) have come for a visit in the old town. Originally they came from the frontispiece in my mother’s copy of “A Child’s Garden of Verses” by Robert Louis Stevenson (signed to her by my great great grandfather who appears as a baby in the first panel, on the back of Emeline Netter). I have painted these children many times over the years. Sometimes they appear innocent, quizzical, whimsical. Other times they manage a precarious existence, living under ground, in trees, between worlds.

The ghosts rise not just from the Natchez Cemetery, but also from the site of the so-called ‘contraband camp’ referred to as The Corral. The camp was set up by an under-prepared Union army when it found itself over-run by slaves fleeing the plantations in the surrounding county. The Union army had no plan to house or protect the newly freed men, women and children, so they created a temporary camp, where an unknown number of African Americans perished from starvation and disease. The number dead is understood to be between one and three thousand. Those that managed to survive did so with nothing more than in-season peaches for sustenance. The discarded pits grew into a grove of peach trees which stands as the only marker to the tragedy.

The grandmother of a friend drives her Plymouth, as she always did, to watch the sun set from the bluff.

Related Images:

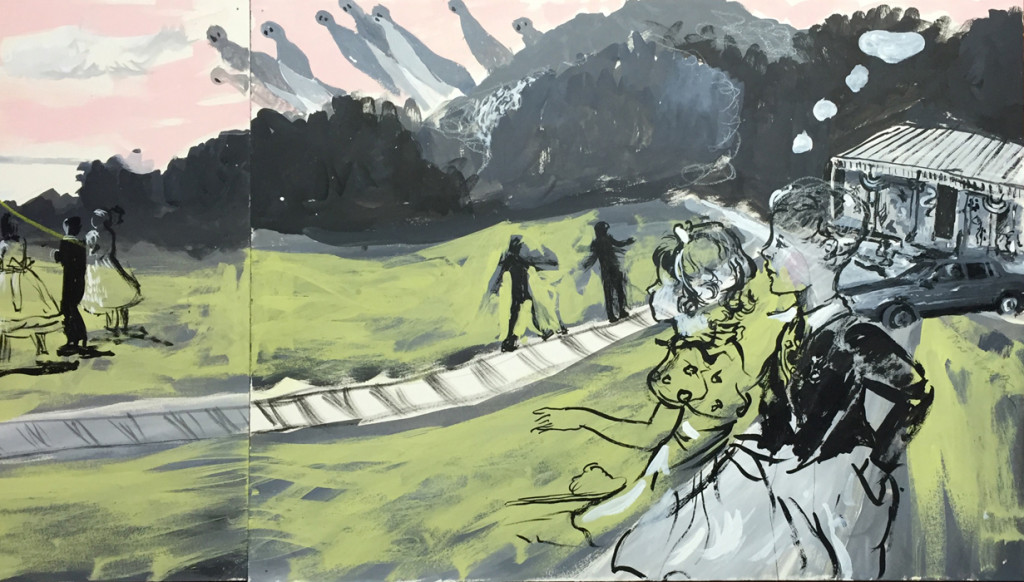

Natchez Bluff (panel 16)

Natchez Bluff (panel 15)

XV.

A hot air balloon with presumably a very anxious passenger.

The train engine is one that actually just sold at auction. It used to run on the track from Natchez to nearby Washington, MS.

According to maps in the Historic Natchez Foundation archive, the old train round-table existed on this spot. Those who are familiar with the Natchez Pageant will recognize the ‘placard bearers’ and their paired rotation. Elysium, the Elysian Fields, is the idyllic afterworld for the blessed and fortunate. For a place with so few actual Greeks, the Hellenic sensibility shows well in the Antebellum South.

A giant possum sings “Won’t you come home Bill Bailey, won’t you come home,” presumably in time with the calliope player a few panels back.

Related Images:

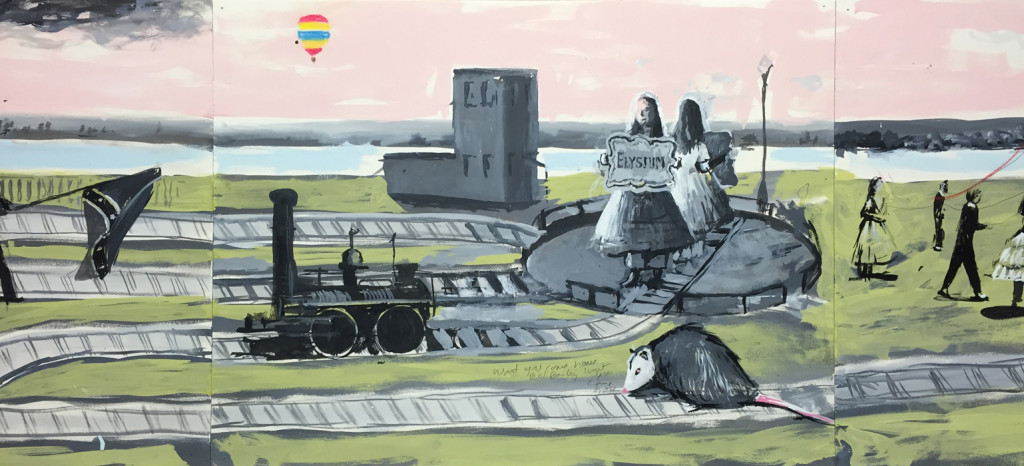

Natchez Bluff (panel 14)

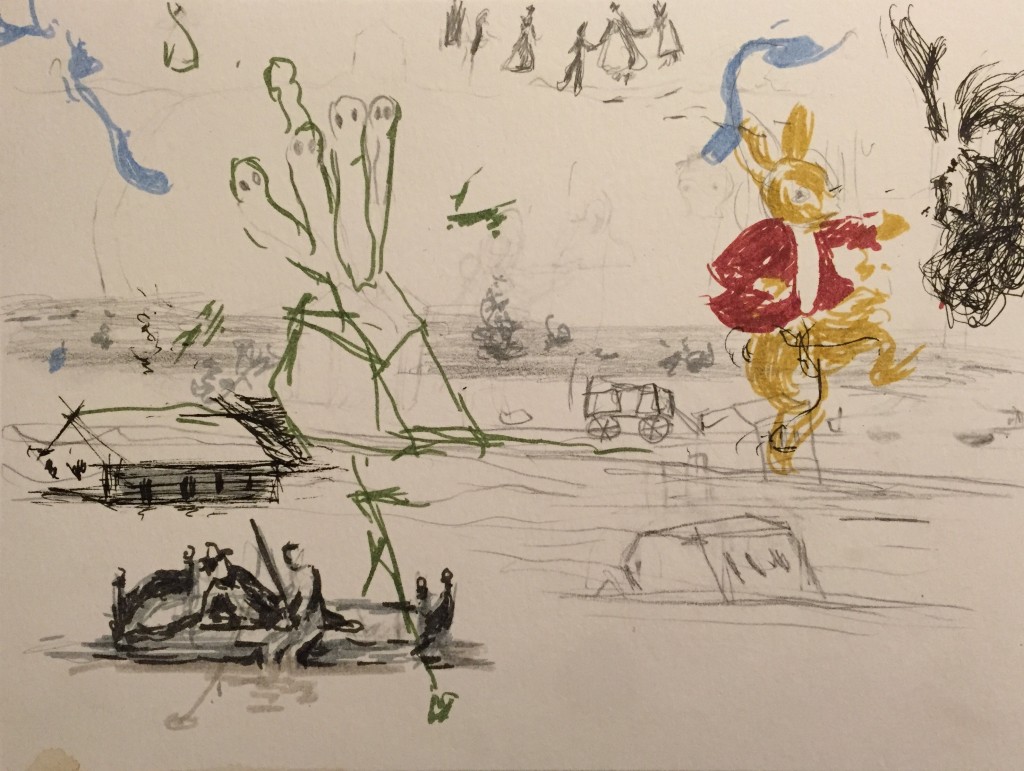

XIV.

A monstrous tornado that struck Natchez in 1840 killed 317, mostly those Under-the Hill, tossing boats out of the river, sometimes considerable distances.

A tableaux from the Natchez Pageant that celebrated the various National flags that have flown over Natchez. Notably the Confederacy was considered a nation whose standing equalled that of Spain, Britain, France, and the United States. As recently as 2014, there were still Confederate Flag Runners as part of the Garden Club Courts. That is preposterous.

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 13)

Natchez Bluff (panel 12)

XII.

A man playing the calliope. Calliope was the most eloquent of all Muses in Greek Mythology. When a steamboat would dock, the sound of the steam calliope could be heard all over town. Jumpy ragtime melodies, loud and warped, were both lovely and grotesque.

Family letters and diaries describe various scourges of Yellow Fever that took many lives, often children’s. Of the letters that survive from my family members in Natchez, seventy percent (let’s say) are about different illnesses and symptoms, boils and broken limbs. Consumption and cholera. The rest is about sewing, the weather, and wishing that to whomever the letter was written would come home.

Natchez Indians stand beneath the divine sun.

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 11)

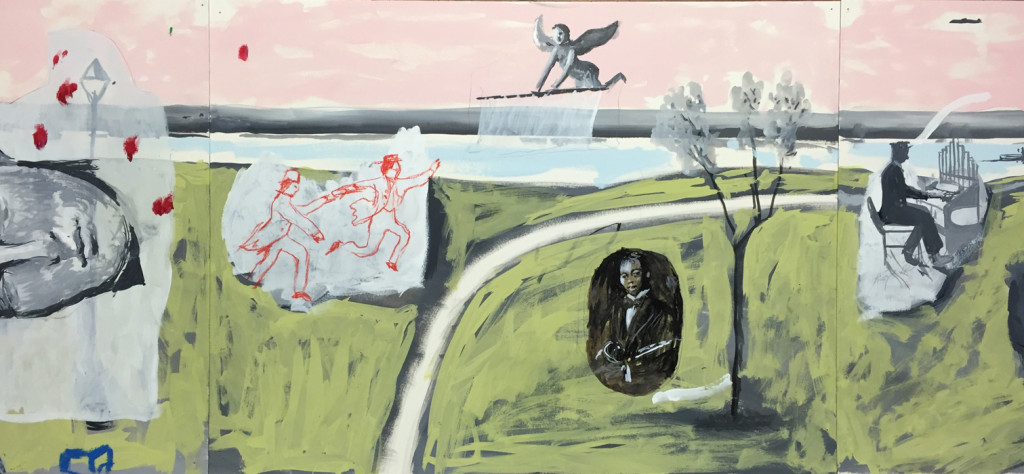

XI.

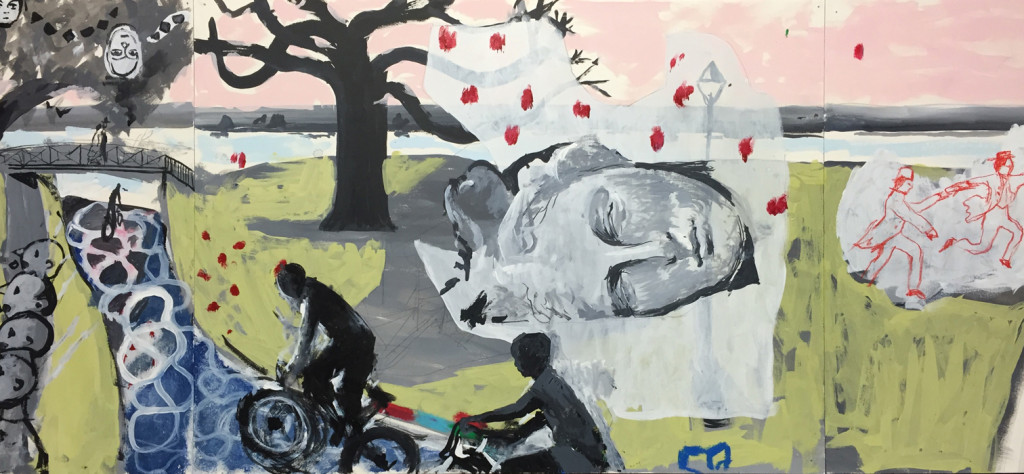

The two red figures are from a drawing by William Johnson, the famous “Barber of Natchez.” He described and then illustrated in his diary a fist fight that he witnessed in the street.

The cherub is from a 17th century French map of New Orleans, conceivably there could have been one of Natchez. The pudgy celestial infant appears to be dragging the River. Goodness knows what will turn up.

The portrait is of Walter Barnes, the beloved band leader whose orchestra drew a crowd of hundreds to the Rhythm Club on St. Catherine Street on April 23, 1940. The night ended in a devastating fire, killing 209 people, mostly African American. My great great grandfather’s house was just a few blocks away on N. Union and he went the next morning with many others to see the bodies.

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 10)

Natchez Bluff (panel 9)

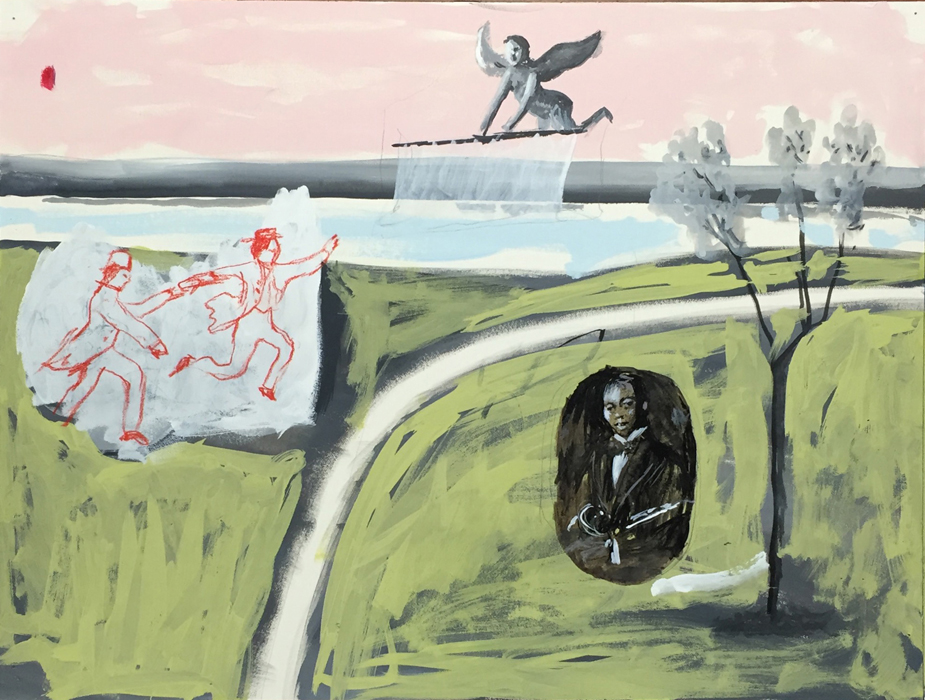

IX.

The barber scene is from an FSA photograph taken by Ben Shahn in the New York Public Library Archive. In the background you can see that they were on the bluff, right around this area.

Itinerant preachers used to go around the South teaching shaped note singing, a complex harmonic singing using shapes to denote different tones. They used The Sacred Harp Hymnal; the recordings I’ve heard are otherworldly. My grandfather used to talk about the Sacred Harp gatherings. The preacher here sings from the hymnal: “And alas did my savior bleed? And did my sov’reign die! Would he devote that sacred head to such a worm as I?”

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 8)

VIII.

There is a long artistic history of anthropomorphized animals, surrogates for human behavior that is hardly human. The mule is from Goya’s Los Caprichos, his series of etchings on war and human error.

The figures on the gazebo came from historical photos in the HNF archive.

The round headed fellow is my great grandfather, Dr. David Smith, who was an optometrist. He disappeared in the early 1920’s and died at Whitfield Hospital in the 1960’s. That’s all I know about that. I have a pamphlet from his optometrist shop and my Grandmother kept a photo of him on her desk, though nothing was ever said about him.

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 7)

VII.

A bed barge. A barge, but it’s a bed.

The hut is from Alexandre de Batz, an 18th century etching of a Natchez Indian dwelling. Next to the hut is scribbled “I can edit this out later”. And I did – originally a group of Klansmen having a picnic.

This panel and the next depict a scene from the book “Southwest by a Yankee” by Joseph Holt Ingraham (the figure in pen). He describes a slave auction happening on Main Street in Natchez as two slaves stand by watching. Ingraham overheard them discussing what they were bought for, compared to the man on the auction block.

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 6)

Natchez Bluff (panel 5)

V.

Ascending Silver Street we have a carnivalesque group – notably, this is the only panel in which the Klan appears; though several Klan references existed elsewhere but were painted out.

A horse with a bullwhip, the French Explorer La Salle.

The young woman with unborn child is Louise the Unfortunate, who was said to be haunting the third floor of my Grandparents’ house where they both died in childbirth. Her gravestone is in the Natchez cemetery with only “Louise the Unfortunate” engraved. My grandfather bought the plot next to her and his stone reads “I Was Here But Now I Haint.”

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 4)

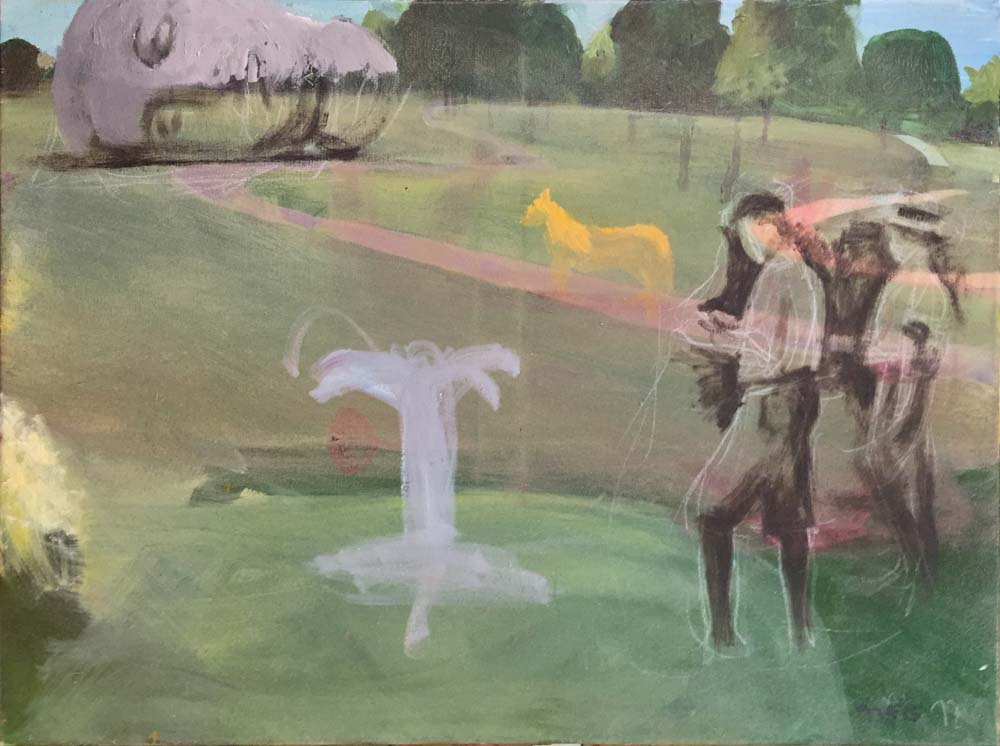

IV.

There’s me, Julia, Vivian and Gus having a picnic, a snake minding his own business.

The two figures in the back are from the Historic Natchez Foundation archive from roughly that spot in the 19th century. The group of four African Americans is from the NYPL Farm Security Administration archive.

The hot air balloons are a yearly thing in Natchez. I remember one year standing on the bluff at Rosalie, watching one burst into flames and crash into the river. Did I dream that?

Related Images:

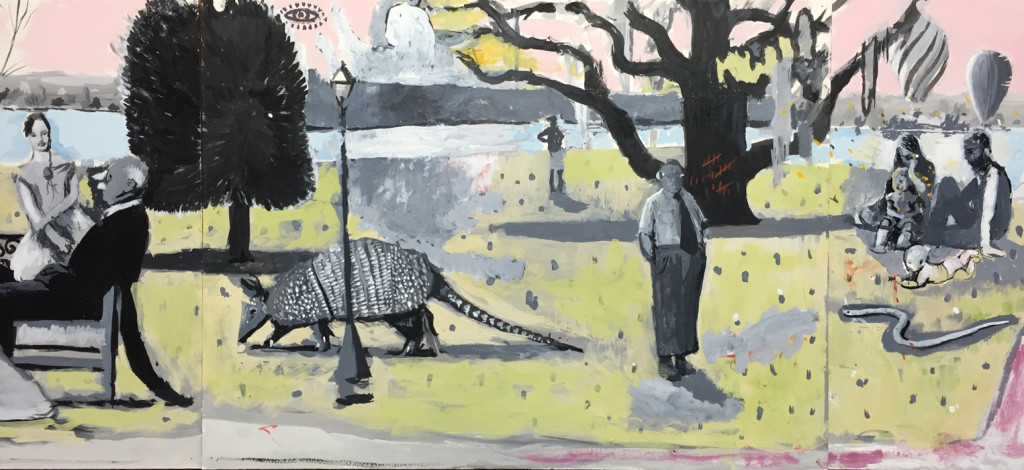

Natchez Bluff (panel 3)

III.

A very large dinosaur-like armadillo.

Locals might remember C.T. Kelly who stood on street corners all over town, often he appeared to bi-locate. You’d be downtown and he’s there on the corner of Main and Commerce, rocking on his heels, jingling change in his pockets. You’d go out to the mall and there he is again, doing the same. Lime green pants and wide plaid tie, accusing somebody of being a communist.

In the distance, a Natchez Indian watching a sunset, or divine eye.

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 2)

II.

The shoe-shine vignette is from the Farm Security Administration photographs in Natchez in the 1930’s. Taken by Marion Post Wolcott, in the New York Public Library archive.

The large group is from a photograph of my great great grandfather (the baby from the previous panel), his wife and three granddaughters (one of them my Grandmother) which hung in my grandparents’ dining room. He was referred to by multiple generations as “Grandfather,” which I found confusing. He was formal, sentimental and uncompromising; he took in my grandmother and her sisters when their father “died” (see panel 8). I’ve always assumed I got my body shape from him, but his penmanship was much better. He was an exhaustive keeper of family history, or shaper of family myth, however you like.

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff (panel 1)

I.

Here we see the Natchez Indians attacking the French in 1729 at Fort Rosalie, now the house called Rosalie, seen in the background. The French retaliated by slaughtering nearly every last member of the sun-worshiping tribe. We used to play in the yard there quite a bit, a gorgeous view of the River.

My great great grandfather writes in his memoirs about fleeing Natchez as a child during the Civil War with their ‘trusted nurse Emeline Netter,’ which is a quaint way to refer to someone who was almost definitely a slave. According to some spotty census records, she would have been in her early twenties when the War started. I see the figures in the distance as the baby ancestor on Emeline’s back.

Related Images:

Natchez Bluff

![]()

*Scroll right to see full frieze

Natchez Bluff

Noah Saterstrom | gouache on paper on masonite | 12″ x 272″ (in 17 panels) | 2016

Natchez Tricentennial Celebration, Historic Natchez Foundation, Jan 28 – Feb 28

The high stretch of bank overlooking the Mississippi River along what is now Broadway Street in Natchez is referred to by locals simply as the Bluff. Designated for public use by the Spanish in the 1700’s, it has been protected as a promenade ever since. My grandparents lived at a house called Edelweiss which sits at the top of Silver Street, looming over the bluff and the water beyond; there is no view in the world more familiar to me than the River from that vantage.

This “Natchez Bluff” painting is a tribute to the many and varied lives lived along the physical bluff from the advent of civilization in the area to the days I picnicked there with my family. It includes both the wartime atrocities that carved the human history of the cliff and the leisure class strolls that have had the panoramic view of the River as a backdrop.

I also use “Bluff” for its other meaning: deception, pretense, facade. Historically, any celebration of Natchez was a carefully curated, fanciful, whitewashed depiction of what the original Natchez Confederate Pageant program of 1952 calls the “halcyon days before ’61.”

The Natchez that I grew up in indeed appeared bucolic and serene, a slow waltz choreographed by an old Mississippi ancestry that left a legacy of aristocratic self-worth without any actual wealth. My experience of Natchez was guided by Victorian principles that valued formality, elegance and politeness, often at the expense of honesty. I felt society (outside of my immediate family) was hostile to difference and there was a silent, relentless reinforcement of class roles that left me with a vague unease. Despite that somewhat sinister undercurrent, for me life in Natchez was essentially safe and beautiful.

I lived the life of that powerful, crumbling ruling class aristocracy, and therefore, I know I am fundamentally unable to truly see Natchez from any other point of view. And as we see, not just in Natchez, or in Mississippi, or in the South, but all over the country, those with privilege (mostly white people – and of course I include myself) are ignorant of the extent of their privilege and the obstacles others face. The best we can do is to listen, closely and without preconception, to the stories others tell in an attempt to make delicate work of incorporating narratives other than our own in the service of honest exploration and exposition.

In researching for the making of this piece, as I talked with people about their memories, sifted through photography archives, and read of life on the Bluff, I was struck again with the fact that there is not one Natchez, but many. The outline of these realities, too, is not sharply hewn, nor is it split evenly between races; rather, it exists on an overlapping spectrum of lives lived. All whites did not experience the same town, neither did all blacks, and it is, I think, damaging to simplify in either direction.

Yet, regardless of these extant complexities, only one version has often been used to portray the town – or rather, one version of one of the versions of Natchez.

If the only voice in town is the remnant of a nostalgic aristocracy, the best we can hope for is illusion and romance. Songbirds and fragrant honeysuckle.

Fortunately, the old regime of Natchez, which would have only told one story, is now, and increasingly, accompanied by many new voices. I hope to add my own with its insistence that it is possible to celebrate Natchez by focusing on the real town, its actual history and complexity, and not reduce it to fiction.

For a town so small and remote, it is a place of great national contradiction, known for enormous wealth and devastating poverty, elegant sophistication and stark brutality.

The town draws some people in as it simultaneously shuts others out and keeps many down.

It has transcendent physical beauty; it is a rich tapestry composed of natural features and those created by centuries of human hands.

It is a region shaped and molded by devastating effects of greed, fear and human ignorance: DeSoto’s ruinous arrival. The French colonist’s decimation of the Natchez Indians. The massive and brutal slave trade. Jim Crow era oppression.

It has witnessed natural tragedies in the scourges of Yellow Fever in the 19th century, and the Great Tornado of 1840 while succumbing to catastrophic human errors, like the thousands of unnamed, unmarked dead at the so-called “Corral” contraband camp during the Civil War and the hundreds of revelers burned in the Rhythm Club fire of 1940.

My intention and my hope is to focus not only on the difficult stories of Natchez, nor the crumbling aristocratic facade, but to work with the richness and contradiction to pave avenues of reflection and recognition. Art, according to some, is best used to open questions, to lengthen the resonance of those questions, not to answer them.

While it is perhaps not entirely deceitful to show Natchez as the romantic home of the antebellum planter class, it is a problem to show nothing else, as was once the case. We can and should rejoice that things are changing, stages are opening, and narratives are expanding; this new reality, in itself, is a cause for celebration.

– Noah Saterstrom, 2016

***

I’ll be posting the 17 panels from now until the show opens next week. The accompanying text is a sort of ‘key’ for each panel. Generally, I don’t think paintings need explanations, but this work is full of specific allusions that may be of interest.

Deepest gratitude to the Historic Natchez Foundation and the Tricentennial Committee for inviting me to show this work. And I’d also like to thank those who helped me research and offered their personal stories without hesitation: Antionette Thompson, Wesley Nichols, Ruth and Charlie Powers, David Abbott (Mississippi Dept of Archives and History), David Lowe (New York Public Library Photography Archive), Mimi Miller (Historic Natchez Foundation).

The painting is dedicated to my grandparents Margaret and Theo Wesley.

Related Images:

Bird’s Got the Word no. 6

![]()

Related Images:

Bird’s Got the Word no. 5

![]()

Related Images:

Bird’s Got the Word no. 4

![]()

Related Images:

Bird’s Got the Word no. 3

![]()

Related Images:

Bird’s Got the Word no. 2

![]()